Multi-leader Replication (Master–master or Active/active Replication)

Although replication architectures with only a single leader is a common approach, there are interesting alternatives.

Leader-based replication has one major downside: there is only one leader, and all writes must go through it. If you can’t connect to the leader for any reason, for example due to a network interruption between you and the leader, you can’t write to the database.

A natural extension of the leader-based replication model is to allow more than one node to accept writes. Replication still happens in the same way: each node that processes a write must forward that data change to all the other nodes. We call this a multi-leader configuration (also known as master–master or active/active replication). In this setup, each leader simultaneously acts as a follower to the other leaders.

Use Cases for Multi-Leader Replication

It rarely makes sense to use a multi-leader setup within a single datacenter, because the benefits rarely outweigh the added complexity. However, there are some situations in which this configuration is reasonable.

Multi-datacenter operation

Imagine you have a database with replicas in several different datacenters (perhaps so that you can tolerate failure of an entire datacenter, or perhaps in order to be closer to your users). With a normal leader-based replication setup, the leader has to be in one of the datacenters, and all writes must go through that datacenter.

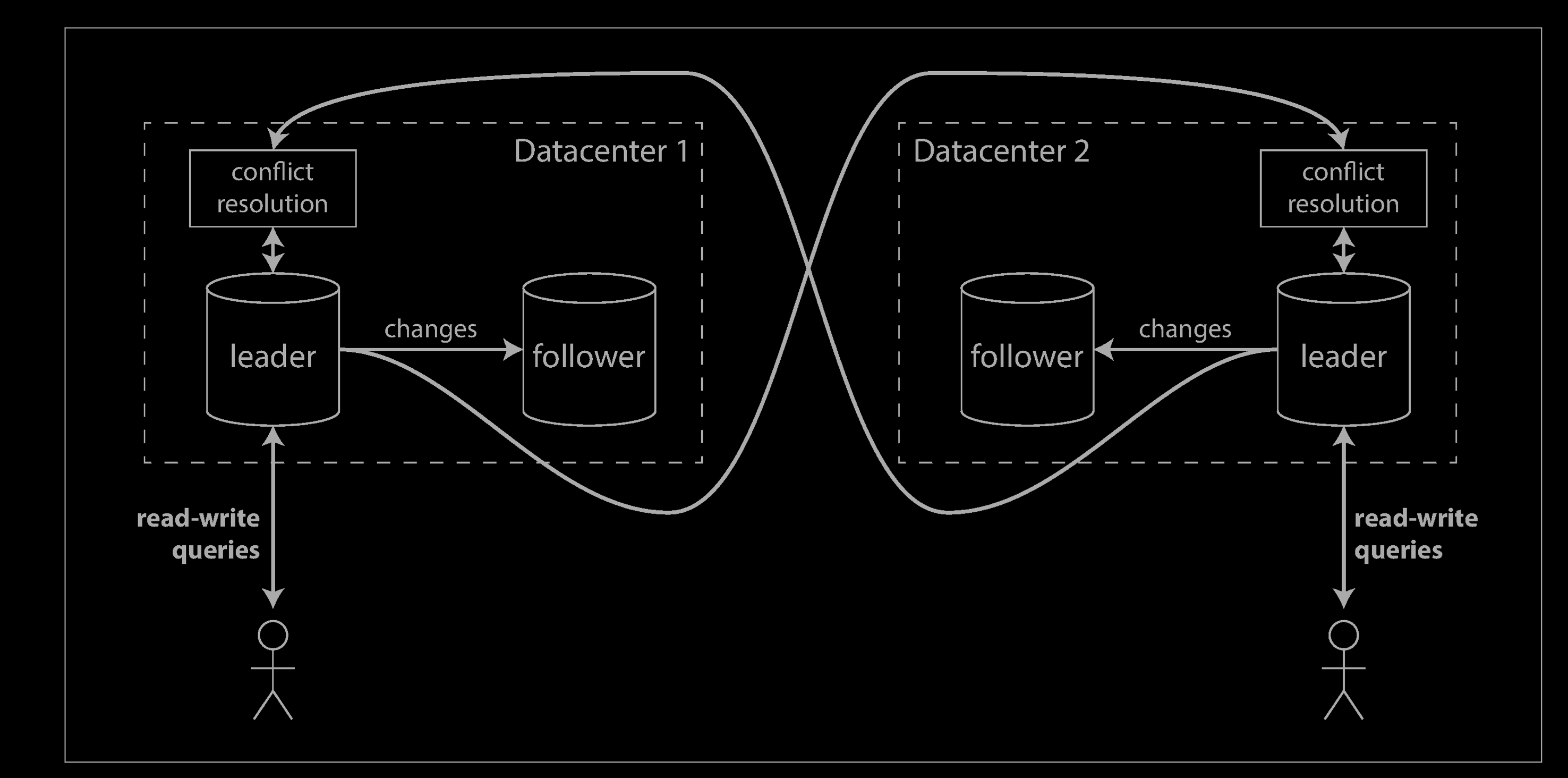

In a multi-leader configuration, you can have a leader in each datacenter. The figure below shows what this architecture might look like. Within each datacenter, regular leader–follower replication is used; between datacenters, each datacenter’s leader replicates its changes to the leaders in other datacenters.

Comparison Between multi-leader and single-leader

Let’s compare how the single-leader and multi-leader configurations fare in a multi-datacenter deployment:

Performance

In a single-leader configuration, every write must go over the internet to the datacenter with the leader. This can add significant latency to writes and might contravene the purpose of having multiple datacenters in the first place. In a multi-leader configuration, every write can be processed in the local datacenter and is replicated asynchronously to the other datacenters. Thus, the inter-datacenter network delay is hidden from users, which means the perceived performance may be better.

Tolerance of datacenter outages

In a single-leader configuration, if the datacenter with the leader fails, failover can promote a follower in another datacenter to be leader. In a multi-leader con‐figuration, each datacenter can continue operating independently of the others, and replication catches up when the failed datacenter comes back online.

Tolerance of network problems

Traffic between datacenters usually goes over the public internet, which may be less reliable than the local network within a datacenter. A single-leader configuration is very sensitive to problems in this inter-datacenter link, because writes are made synchronously over this link. A multi-leader configuration with asynchronous replication can usually tolerate network problems better: a temporary network interruption does not prevent writes being processed.

Handling Write Conflicts

Scenarios

Some databases support multi-leader configurations by default, but it is also often implemented with external tools, such as Tungsten Replicator for MySQL, BDR for PostgreSQL, and GoldenGate for Oracle.

Although multi-leader replication has advantages, it also has a big downside: the same data may be concurrently modified in two different datacenters, and those write conflicts must be resolved (indicated as “conflict resolution”).

As multi-leader replication is a somewhat retrofitted feature in many databases, there are often subtle configuration pitfalls and surprising interactions with other database features. For example, autoincrementing keys, triggers, and integrity constraints can be problematic. For this reason, multi-leader replication is often considered dangerous territory that should be avoided if possible.

- Clients with offline operation

- Collaborative editing

Clients with offline operation

Another situation in which multi-leader replication is appropriate is if you have an application that needs to continue to work while it is disconnected from the internet.

For example, consider the calendar apps on your mobile phone, your laptop, and other devices. You need to be able to see your meetings (make read requests) and enter new meetings (make write requests) at any time, regardless of whether your device currently has an internet connection. If you make any changes while you are offline, they need to be synced with a server and your other devices when the device is next online.

In this case, every device has a local database that acts as a leader (it accepts write requests), and there is an asynchronous multi-leader replication process (sync) between the replicas of your calendar on all of your devices. The replication lag may be hours or even days, depending on when you have internet access available.

From an architectural point of view, this setup is essentially the same as multi-leader replication between datacenters, taken to the extreme: each device is a “datacenter,” and the network connection between them is extremely unreliable. As the rich history of broken calendar sync implementations demonstrates, multi-leader replication is a tricky thing to get right.

There are tools that aim to make this kind of multi-leader configuration easier. For example, CouchDB is designed for this mode of operation.

Collaborative editing

Real-time collaborative editing applications allow several people to edit a document simultaneously. For example, Etherpad and Google Docs allow multiple people to concurrently edit a text document or spreadsheet.

We don’t usually think of collaborative editing as a database replication problem, but it has a lot in common with the previously mentioned offline editing use case. When one user edits a document, the changes are instantly applied to their local replica (the state of the document in their web browser or client application) and asynchronously replicated to the server and any other users who are editing the same document.

If you want to guarantee that there will be no editing conflicts, the application must obtain a lock on the document before a user can edit it. If another user wants to edit the same document, they first have to wait until the first user has committed their changes and released the lock. This collaboration model is equivalent to single-leader replication with transactions on the leader.

However, for faster collaboration, you may want to make the unit of change very small (e.g., a single keystroke) and avoid locking. This approach allows multiple users to edit simultaneously, but it also brings all the challenges of multi-leader replication, including requiring conflict resolution.

Handling Write Conflicts

The biggest problem with multi-leader replication is that write conflicts can occur, which means that conflict resolution is required.

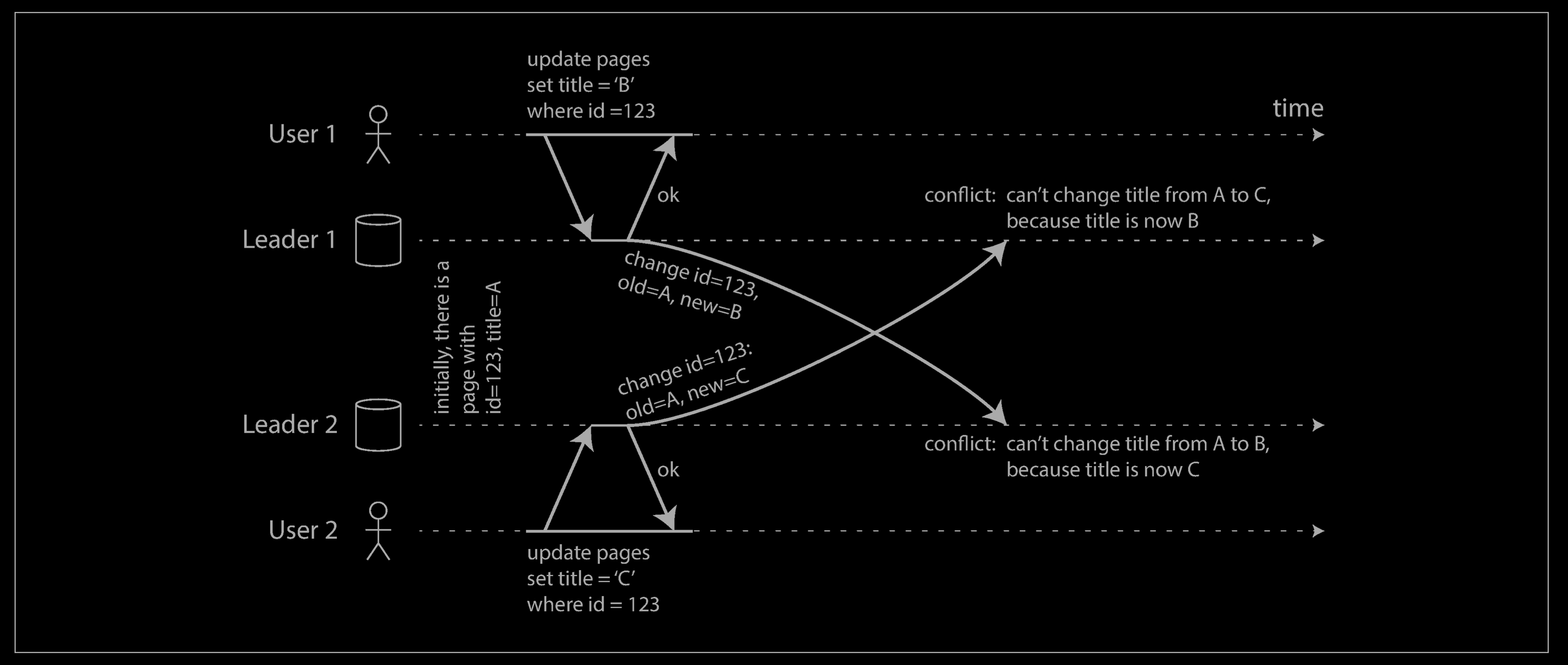

For example, consider a wiki page that is simultaneously being edited by two users, as shown below. User 1 changes the title of the page from A to B, and user 2 changes the title from A to C at the same time. Each user’s change is successfully applied to their local leader. However, when the changes are asynchronously replicated, a conflict is detected. This problem does not occur in a single-leader database.

Synchronous versus asynchronous conflict detection

In a single-leader database, the second writer will either block and wait for the first write to complete, or abort the second write transaction, forcing the user to retry the write. On the other hand, in a multi-leader setup, both writes are successful, and the conflict is only detected asynchronously at some later point in time. At that time, it may be too late to ask the user to resolve the conflict.

In principle, you could make the conflict detection synchronous—i.e., wait for the write to be replicated to all replicas before telling the user that the write was successful. However, by doing so, you would lose the main advantage of multi-leader replication: allowing each replica to accept writes independently. If you want synchronous conflict detection, you might as well just use single-leader replication.

Conflict avoidance

The simplest strategy for dealing with conflicts is to avoid them: if the application can ensure that all writes for a particular record go through the same leader, then conflicts cannot occur. Since many implementations of multi-leader replication handle conflicts quite poorly, avoiding conflicts is a frequently recommended approach.

For example, in an application where a user can edit their own data, you can ensure that requests from a particular user are always routed to the same datacenter and use the leader in that datacenter for reading and writing. Different users may have different “home” datacenters (perhaps picked based on geographic proximity to the user), but from any one user’s point of view the configuration is essentially single-leader.

However, sometimes you might want to change the designated leader for a record—perhaps because one datacenter has failed and you need to reroute traffic to another datacenter, or perhaps because a user has moved to a different location and is now closer to a different datacenter. In this situation, conflict avoidance breaks down, and you have to deal with the possibility of concurrent writes on different leaders.

Converging toward a consistent state

A single-leader database applies writes in a sequential order: if there are several updates to the same field, the last write determines the final value of the field.

In a multi-leader configuration, there is no defined ordering of writes, so it’s not clear what the final value should be.

If each replica simply applied writes in the order that it saw the writes, the database would end up in an inconsistent state: the final value would be C at leader 1 and B at leader 2. That is not acceptable—every replication scheme must ensure that the data is eventually the same in all replicas. Thus, the database must resolve the conflict in a convergent way, which means that all replicas must arrive at the same final value when all changes have been replicated.

There are various ways of achieving convergent conflict resolution:

- Give each write a unique ID (e.g., a timestamp, a long random number, a UUID, or a hash of the key and value), pick the write with the highest ID as the winner, and throw away the other writes. If a timestamp is used, this technique is known as last write wins (LWW). Although this approach is popular, it is dangerously prone to data loss

- Give each replica a unique ID, and let writes that originated at a higher-numbered replica always take precedence over writes that originated at a lower-numbered replica. This approach also implies data loss.

- Somehow merge the values together—e.g., order them alphabetically and then concatenate them

- Record the conflict in an explicit data structure that preserves all information, and write application code that resolves the conflict at some later time (perhaps by prompting the user).

Custom conflict resolution logic

As the most appropriate way of resolving a conflict may depend on the application, most multi-leader replication tools let you write conflict resolution logic using application code. That code may be executed on write or on read:

On write

As soon as the database system detects a conflict in the log of replicated changes, it calls the conflict handler. For example, Bucardo allows you to write a snippet of Perl for this purpose. This handler typically cannot prompt a user—it runs in a background process and it must execute quickly.

On read

When a conflict is detected, all the conflicting writes are stored. The next time the data is read, these multiple versions of the data are returned to the applica‐tion. The application may prompt the user or automatically resolve the conflict, and write the result back to the database. CouchDB works this way, for example.

Note that conflict resolution usually applies at the level of an individual row or document, not for an entire transaction. Thus, if you have a transaction that atomically makes several different writes, each write is still considered separately for the purposes of conflict resolution.

Automatic Conflict Resolution

Conflict resolution rules can quickly become complicated, and custom code can be error-prone. Amazon is a frequently cited example of surprising effects due to a conflict resolution handler: for some time, the conflict resolution logic on the shopping cart would preserve items added to the cart, but not items removed from the cart. Thus, customers would sometimes see items reappearing in their carts even though they had previously been removed.

There has been some interesting research into automatically resolving conflicts caused by concurrent data modifications. A few lines of research are worth mention‐ing:

• Conflict-free replicated datatypes (CRDTs) are a family of data structures for sets, maps, ordered lists, counters, etc. that can be concurrently edited by multiple users, and which automatically resolve conflicts in sensible ways. Some CRDTs have been implemented in Riak 2.0.

• Mergeable persistent data structures track history explicitly, similarly to the Git version control system, and use a three-way merge function (whereas CRDTs use two-way merges).

• Operational transformation is the conflict resolution algorithm behind collaborative editing applications such as Etherpad and Google Docs. It was designed particularly for concurrent editing of an ordered list of items, such as the list of characters that constitute a text document.

Implementations of these algorithms in databases are still young, but it’s likely that they will be integrated into more replicated data systems in the future. Automatic conflict resolution could make multi-leader data synchronization much simpler for applications to deal with.

Multi-Leader Replication Topologies

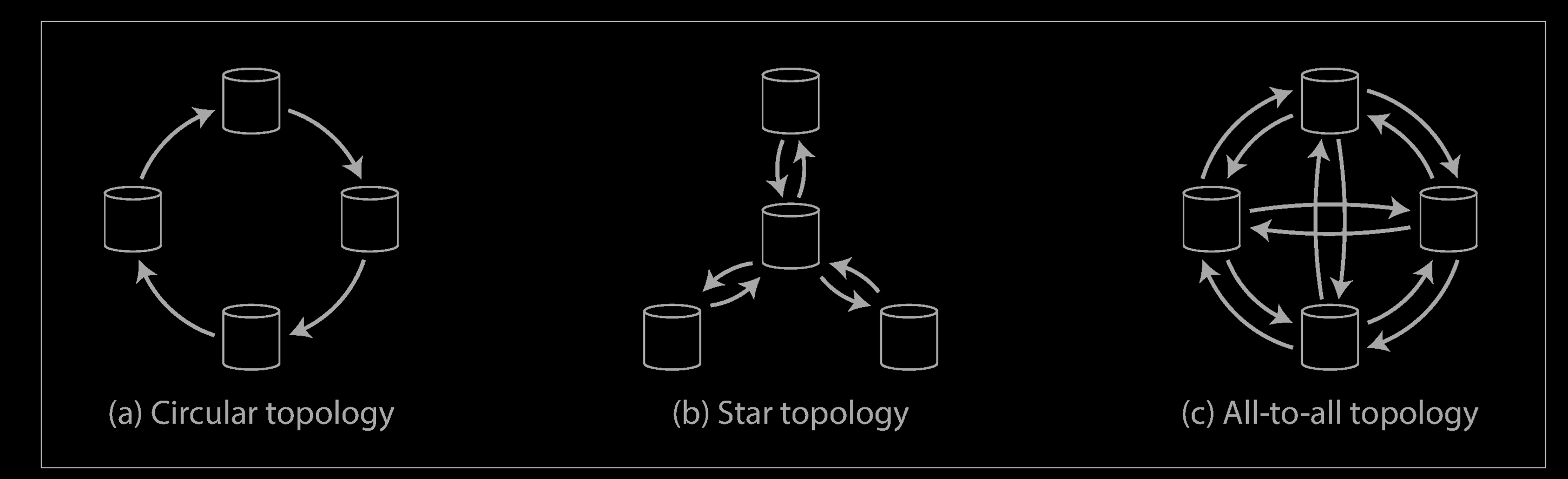

A replication topology describes the communication paths along which writes are propagated from one node to another.

The most general topology is all-to-all, in which every leader sends its writes to every other leader. However, more restricted topologies are also used: for example, MySQL by default supports only a circular topology, in which each node receives writes from one node and forwards those writes (plus any writes of its own) to one other node. Another popular topology has the shape of a star:**** one designated root node forwards writes to all of the other nodes. The star topology can be generalized to a tree.

In circular and star topologies, a write may need to pass through several nodes before it reaches all replicas. Therefore, nodes need to forward data changes they receive from other nodes. To prevent infinite replication loops, each node is given a unique identifier, and in the replication log, each write is tagged with the identifiers of all the nodes it has passed through. When a node receives a data change that is tagged with its own identifier, that data change is ignored, because the node knows that it has already been processed.

A problem with circular and star topologies is that if just one node fails, it can interrupt the flow of replication messages between other nodes, causing them to be unable to communicate until the node is fixed. The topology could be reconfigured to work around the failed node, but in most deployments such reconfiguration would have to be done manually. The fault tolerance of a more densely connected topology (such as all-to-all) is better because it allows messages to travel along different paths, avoiding a single point of failure.

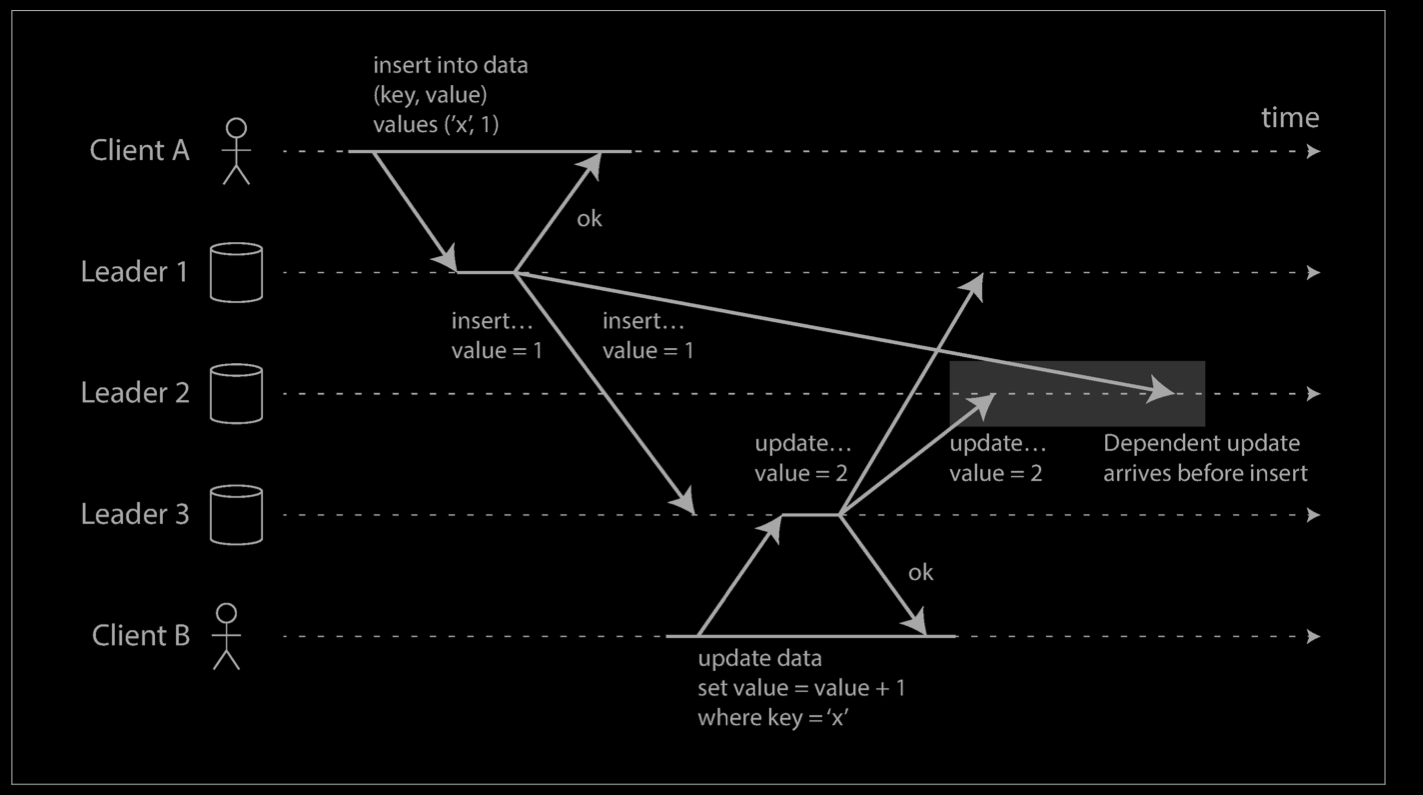

On the other hand, all-to-all topologies can have issues too. In particular, some network links may be faster than others (e.g., due to network congestion), with the result that some replication messages may “overtake” others, as illustrated below.

In this example, client A inserts a row into a table on leader 1, and client B updates that row on leader 3. However, leader 2 may receive the writes in a different order: it may first receive the update (which, from its point of view, is an update to a row that does not exist in the database) and only later receive the corresponding insert (which should have preceded the update).

This is a problem of causality: the update depends on the prior insert, so we need to make sure that all nodes process the insert first, and then the update. Simply attaching a timestamp to every write is not sufficient, because clocks cannot be trusted to be sufficiently in sync to correctly order these events at leader 2.

To order these events correctly, a technique called version vectors can be used. However, conflict detection techniques are poorly implemented in many multi-leader replication systems. For example, at the time of writing, PostgreSQL BDR does not provide causal ordering of writes, and Tungsten Replicator for MySQL doesn’t even try to detect conflicts.

If you are using a system with multi-leader replication, it is worth being aware of these issues, carefully reading the documentation, and thoroughly testing your database to ensure that it really does provide the guarantees you believe it to have.

Version Vectors

Refer to https://swsmile.info/post/Distributed-System-version-vector/

Reference

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Replication_(computing)

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications: The Big Ideas Behind Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Systems

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multi-master_replication